- Home

- Dave Crehore

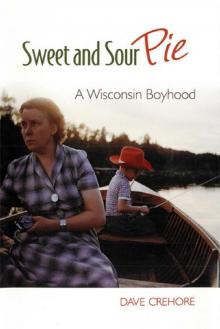

Sweet and Sour Pie: A Wisconsin Boyhood

Sweet and Sour Pie: A Wisconsin Boyhood Read online

Sweet and Sour Pie

Terrace Books, a trade imprint of the University of Wisconsin Press, takes its name from the Memorial Union Terrace, located at

the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Since its inception in 1907, the Wisconsin Union has provided a venue for students, faculty, staff, and alumni to debate art, music, politics, and the issues of the day.

It is a place where theater, music, drama, literature, dance, outdoor activities, and major speakers are made available to the campus and the community.

To learn more about the Union, visit www.union.wisc.edu.

Sweet and Sour Pie

A W i s c o n s i n B oy h o o d

l

D ave C r e h o r e

T e r r a c e B o o k s

A t r a d e i m p r i n t o f t h e U n i v e r s i t y o f W i s c o n s i n P r e s s

Terrace Books

A trade imprint of the University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

www.wisc.edu/wisconsinpress/

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

Copyright © 2009

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a Web site without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

1

3

5

4

2

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Crehore, Dave.

Sweet and sour pie : a Wisconsin boyhood / Dave Crehore.

p.

cm.

ISBN 978-0-299-23060-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-23063-0 (e-book)

1. Crehore, Dave—Childhood and youth.

2. Manitowoc (Wis.)—Biography.

3. Manitowoc (Wis.)—Social life and customs.

I. Title.

F586.42.C74C74

2009

977.5´67—dc22

[B]

2008039538

Disclaimer

In the interest of privacy, respect, and common sense,

many names of people and places that appear in this book have been changed, and some characters and events are composites.

l

To

Mom and Dad,

and

small-town people everywhere.

Contents

Acknowledgments

ix

Beans for Breakfast

3

The Fannie Farmer Mystery

22

The Viggle Years

32

The Christmas When a Lot Happened

40

The Digging Out of Nip

73

The Century Run

81

Sacrificing Sweet Sixteen

93

The Fine Art of Forgetting

97

The Secret Smallmouth Lake in the U.P.

102

The Butternut Buck

110

The Celebrated Water Witch of Door County

117

Lucky Thirteen

126

How Now, Frau Blau?

131

The Dorking Rooster-Catcher

141

The Man of Action

152

No Fair!

161

The Wanderer

172

vii

Contents

Sweet and Sour Pie

183

Envoi

190

Glossary

193

viii

Acknowledgments

Readers of this book will ask themselves how a kid managed to

remember so much. The answer is that Mom and Dad did most of

the remembering. My recollections of the fun and tribulation of our early years together—our Christmases and Thanksgivings, our hunting and fishing trips, and our lost dogs, along with so much else—are rooted in family tales that were told at the fireside or around the kitchen table, after Mom poured us a second cup of coffee and said,

“Do you remember the time . . .”

So, thanks to you, Mom and Dad, for your memories and your

willingness to share them. And thank you for not buying a television set until 1959. A home free of the tube gave the three of us time to read and dream, to talk and listen, to wander in the woods and learn the birds and the trees.

Further acknowledgements are due to a couple of corporations

and a very important person.

First, thanks to the Eastman Kodak Company for manufacturing

Kodachrome slide film. Some of the stories in this book were inspired and verified by slides Dad took in the forties and fifties, images that are as sharp and colorful today as they were back then. I wonder if digital pictures made today will be as useful, or even in existence, fifty or sixty years from now.

ix

Acknowledgments

Second, thanks of a sort to the telephone companies of the fifties.

Long-distance calls were expensive and time-consuming in those

days, so we wrote letters to each other, letters that became lasting, written records of our lives. Few experiences are as bittersweet as discovering, in the papers of a deceased grandfather, a stack of one’s childhood letters to him, carefully preserved and held together with a red rubber band.

Finally, voluminous thanks go to my wife, Joanne, for her sup-

port during the writing of this book. Many book acknowledgements contain that line—“thank you for your support”—without explaining it. In this case, support meant reading and re-reading, out loud, the many drafts of these stories, so that I could correct their sound.

It also meant mowing the lawn, doing the dishes, and cleaning the house while I was engaged in the holy process of writing. So thanks again for your support, Jo. I can hardly wait to start another book.

E arlier versions of some of the stories in this book have been previously published.

“The Fine Art of Forgetting,” “How Now, Frau Blau?” “The

Dorking Rooster-Catcher,” and “The Man of Action” were published in Shooting Sportsman magazine and in Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine.

“The Viggle Years,” “The Digging Out of Nip,” “The Century

Run,” “Sacrificing Sweet Sixteen,” “The Secret Smallmouth Lake in the U.P.,” “The Butternut Buck,” “The Celebrated Water Witch of

Door County,” and “Sweet and Sour Pie” were published in Wiscon-

sin Natural Resources magazine.

The remaining six stories, as well as “Envoi” and the “Glossary,”

appear here for the first time.

x

Sweet and Sour Pie

l

Beans for Breakfast

L et’s find a church that looks like it’s paid for,” Dad said. “An old one without a mortgage.”

Tuesday, August 15, 1950, was our second day in Manitowoc,

Wisconsin. Mom, Dad, our beagle, Rip, and I were scouting the

town in our Studebaker Champion; Dad drove while Mom paged

through the phone book and plotted our position on a map. Our

mission that morning was to locate a Met

hodist church, the A&P, and a store that sold bed frames.

I was seven and shared the back seat with Rip. As we cruised up

one street and down another, Mom and Dad were having a good

time, pointing out taverns with interesting names: the Stop and Go Inn, Leof ’s Spa, the Wonder Bar, the Foam Tavern, the Gay Bar, and the Tip Top Tap.

“Sure are a lot of them,” Dad said.

3

Beans for Breakfast

Mom opened the Yellow Pages to “Taverns” and started to count,

pursing her lips and running a pencil down the long list. “There are eighty-five, to be precise,” she said. She flipped back to “Churches”

and counted again. “And twenty-three churches.”

“It’s the eternal struggle,” Dad said. Mom laughed, and I was surprised that she and Dad were in such high spirits, because the past twenty-four hours had been rough on them.

The movers had arrived the day before, a couple of hours after we did. The marine engineering company Dad worked for had trans-ferred him to Manitowoc from Lorain, Ohio, a steel mill and shipyard city on Lake Erie. They had hired an outfit called Budget Boys to do the moving, and we soon found out how the Budget Boys got

their name: they filled our house with boxes but didn’t unpack them.

As soon as the van was empty, the driver demanded Dad’s signature on the moving contract and started the engine. When Dad pro-tested, the driver pointed to some fine print, let in his clutch, and hit the road.

“Buncha cheapskates,” Dad muttered, meaning the Budget Boys,

his employer, or maybe both.

All we could do was go back in the house and start rummag-

ing. In Ohio, Mom had labeled each box with its destination in

Manitowoc—living room, kitchen, master bedroom, dining room.

But the Budget Boys hadn’t read Mom’s labels, so practically every box and piece of furniture had to be moved again from one room

to another. Luckily for us, in their rush to get going the Boys left a furniture dolly behind. We claimed it as a spoil of war and used it for years.

Dad started trundling boxes back and forth, upstairs and down.

After an hour or so he called from upstairs.

“Charlotte, is our bed frame in the living room? It should be in a long narrow box. Look for Davy’s, too.”

4

Beans for Breakfast

Mom dug around in the maze of cartons and furniture. “I see the

mattresses and springs, but no frames,” she said. “Oh, for cripes sake,” Dad said. “They must have left them in Lorain. We’ll have to buy new ones tomorrow. Now I’m definitely going to keep this

dolly.”

It was getting dark and pretty cold for August. Dad and Mom

lugged the mattresses upstairs. While Dad started a coal fire in the big furnace in the basement, Mom found a wool blanket and a war

surplus GI sleeping bag, and we went to bed without supper. I spent the night in the sleeping bag and it was kind of fun, like camping indoors. Mom and Dad tried to cover themselves with the blanket, which was barely big enough for two.

Mom lay awake most of the night, shivering and staring at the

ceiling. She finally dropped off about four in the morning, but when the first hint of dawn filtered into the bedroom, she woke up, turned on her side, and recoiled in horror.

A large bat was hanging on the wall about four feet away.

“Dammit, there’s a bat!” she yelled. “Dave, wake up, there’s a bat on the wall!” She pulled the blanket away from Dad and tried to

hide under it.

Wrenched from a deep sleep, Dad rolled off the mattress and

landed on his back. He staggered to his feet and hitched up the

baggy undershorts he had slept in. Mom kept on complaining from

under the blanket.

“All right, all right,” Dad said. “I see it!”

“Good!” Mom said. “Now get rid of it!”

“OK,” Dad said, shaking off the last of his sleep. “I’ll figure out something, and in the meantime, Charlotte, be quiet. You’ll just scare it.”

“I don’t care,” Mom said. “It scared me first!”

The racket woke me up, and I walked down the hall from my

5

Beans for Breakfast

room to see what was going on. Rip, who had been sleeping on a

corner of my bedroll, yawned and stretched and followed me. I took in the situation—the bat on the wall, Dad matching wits with it, Mom under the blanket—and came up with a solution that would

be obvious to any seven-year-old boy.

“I know where the pistol is!” I said. I had watched the movers

pack Dad’s .22 Colt Woodsman and thought I could find the box it was in.

“No, no,” Dad said. “We’re not going to start shooting holes in

the walls on our second day in Wisconsin. Besides, I don’t know

where the ammunition is.”

Then his face brightened. “I’ve got it!” he said. He turned to me.

“Hang on to Rip, stay right where you are, and don’t make that bat fly,” he said. “Just leave him alone.”

Dad went downstairs, out the front door, and across the lawn to

the garage, still barefoot and in his underwear. The movers had put our tools and camping gear in the garage, and in a couple of minutes Dad was back in the bedroom with an old-fashioned corn popper, a long-handled wire basket with a sliding metal lid.

“Charlotte, not a sound,” he whispered, and began a stalk, tip-

toeing across the bedroom. With a lightning thrust he clapped the corn popper over the bat and closed the lid, scraping the bat off the wall and into the basket.

“Aha!” Dad exulted. “Charlotte, you can come out now, I’ve got

him!”

Mom’s fingertips appeared, then an eye, an ear, and another eye.

Dad poked the corn popper at her. The bat squeaked and flapped its wings. “See, he’s in here,” Dad said.

Mom pulled the blanket over herself again. “David Roger Cre-

hore,” she said through clenched teeth, “if you intend to keep on sleeping in this bedroom, you will remove that bat, right now!”

6

Beans for Breakfast

“You got it,” Dad said, and went outside to let it go. Wrapped in the blanket, Mom walked warily down the hall to the bathroom, still on the lookout for bats. Before she closed the door, she looked at me and rolled her eyes. “Life in Wisconsin,” she said.

We had a quick, cold breakfast. Mom hunted through boxes in

the living room until she found some canned goods, silverware, her tea kettle, and a couple of ancient tea bags.

“We’ve got a choice,” she said, looking over the cans. “Pork and beans or Ken-L Ration.” Dad hacked open a can of each with his

pocket knife, and we took turns dipping the beans out with tea-

spoons. The lone piece of pork was almost pure fat; we gave it to Rip along with the Ken-L Ration. When the kettle boiled, Dad rinsed

out the bean can, put in a tea bag, poured hot water over it, and handed the can to Mom.

“Would Madam care for a can of tea?” he asked.

“Thank you, Jeeves,” Mom said. She waited a few minutes for it

to steep and took a sip. The surface of the tea had an oil slick from the pork.

“Ahh,” she sighed. “Gracious living in Manitowoc.” Then we hit

the road.

As it turned out, there were two Methodist churches in Mani-

towoc, Saint Paul’s on North Seventh and Wesley on the south side.

Saint Paul’s was a frame building that had probably been paid for in the 1880s. Wesley looked a lot newer. “I vote for Saint Paul’s,” Dad said, and the decision was made.

The A&P wasn’t hard to find, down Eighth Street, Manitowoc’s main drag, and a few blo

cks west on Washington. We bought a loaf of Ann Page bread, a pound of butter, some Eight O’Clock coffee, hamburger, onions, celery, cans of kidney beans and stewed tomatoes, and a tin of cayenne pepper. “If I can find the dutch oven,” Mom said,

“I’ll make a batch of chili to get us through the next couple of days.”

7

Beans for Breakfast

We bought new bed frames at Otto Kuechle’s, a furniture store at Ninth and Jay. Once Mom and Dad had picked out frames that

would fit our mattresses and springs, the salesman folded his arms across his chest, the embodiment of rock-solid integrity.

“I stand behind all the beds I sell,” he said.

“That won’t be necessary,” Dad said. “But I could use some help

getting ’em in the car.”

The Studie was parked outside Kuechle’s front door, and a small

crowd of helpful spectators gathered on the sidewalk as Dad and the salesman rolled down the windows and tried various approaches.

The spectators offered suggestions. One guy got a toolbox from the trunk of his car and offered to take the frames apart; another volunteered the use of his pickup truck.

Finally Dad decided to stow the frames transversely across the

backseat, with the bedposts sticking out of the windows like the can-nons on “Old Ironsides.” When we were ready to go the spectators introduced themselves and petted Rip. There were handshakes all

around, and as we drove off, they waved.

“Nice people,” Dad said. “Small-town people.”

On our way back to the house Dad bought a dollar’s worth of

gas—3.7 gallons—at the Sinclair station on North Eleventh, and we stopped for sundaes at the Park Drug Store on New York Avenue. In the 1950s, if you wanted a sundae you went to the soda fountain at a drugstore.

“You folks new around here?” the pharmacist asked, as he

scooped dishes of vanilla and pumped chocolate syrup over them. It was a small store and the pharmacist doubled as manager and soda jerk.

“We’re just moving in,” Dad said. “Out River Road, up the hill

and to the right.”

“Oh, you mean the old Torrison place,” the pharmacist said.

8

Beans for Breakfast

When we finished our sundaes we headed west. “The old Torri-

son place, eh? Seems like our house has a pedigree,” Dad said. “I wonder when they’ll start calling it the old Crehore place.”

“Never, if I see another bat,” Mom said. She liked to fish and

Sweet and Sour Pie: A Wisconsin Boyhood

Sweet and Sour Pie: A Wisconsin Boyhood